Between the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, driven by the Industrial Revolution, the population of London surged from around one million to more than 2.3 million in less than fifty years. As the city expanded, so too did the need for burial space. Until that point, nearly all burials took place in parish churchyards, which soon became overcrowded and unsanitary. It was not uncommon for new graves to disturb older remains, and in some cases, human bones would resurface during fresh interments. The situation became a growing concern for public health, as decaying bodies polluted water supplies and attracted disease-carrying rats.

To address the crisis, Parliament enacted legislation in 1832 encouraging the creation of private cemeteries on the outskirts of London. Over the next decade, seven large cemeteries were established, designed not just as places of burial but as landscaped spaces of remembrance. In 1852, the Burial Act granted the Secretary of State the power to close London’s overcrowded churchyards to new burials, making these suburban cemeteries the primary resting places for the city's dead. Known collectively as the Magnificent Seven, these cemeteries became a lasting testament to Victorian attitudes toward death, memorialization, and the relationship between nature and the afterlife.

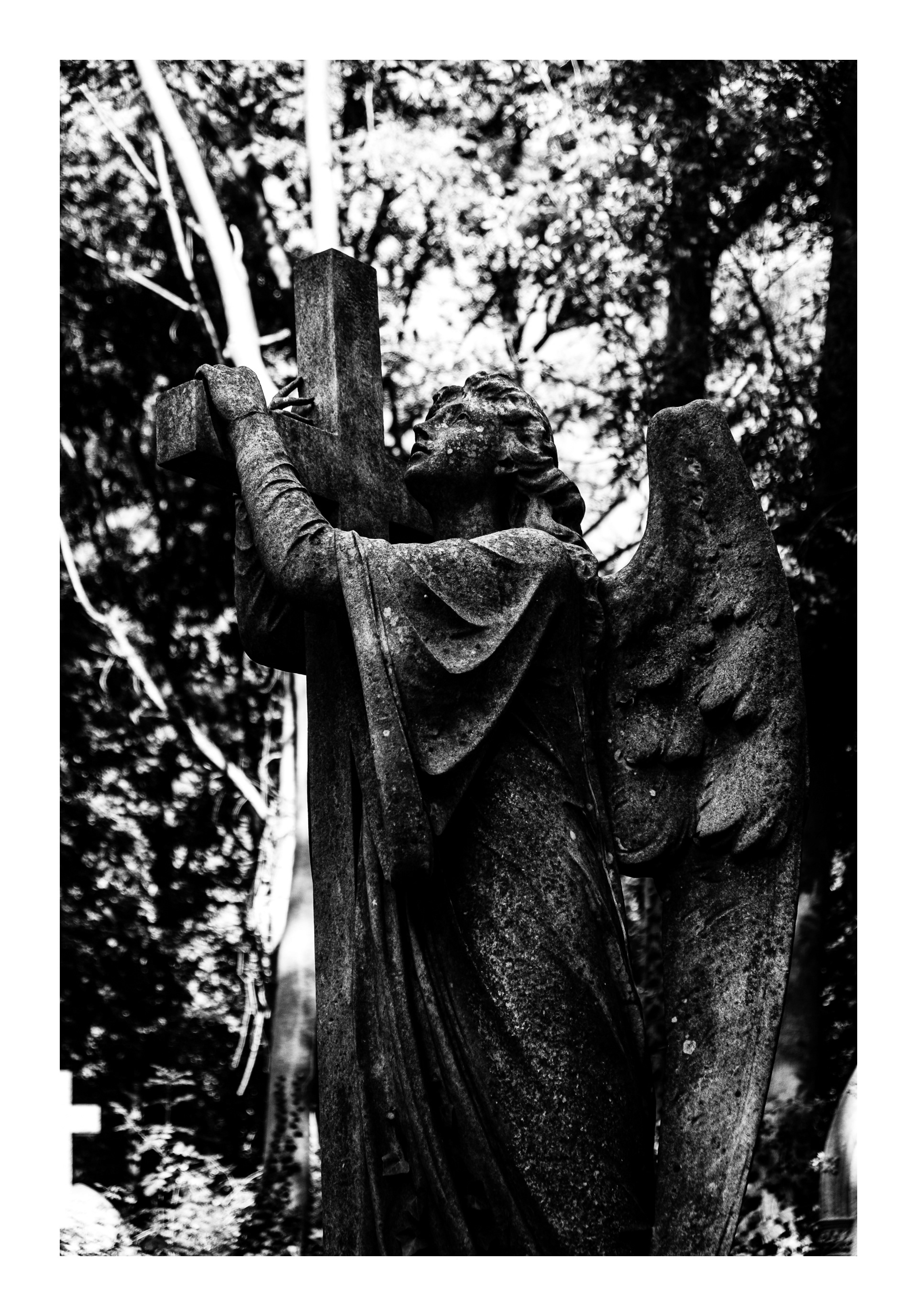

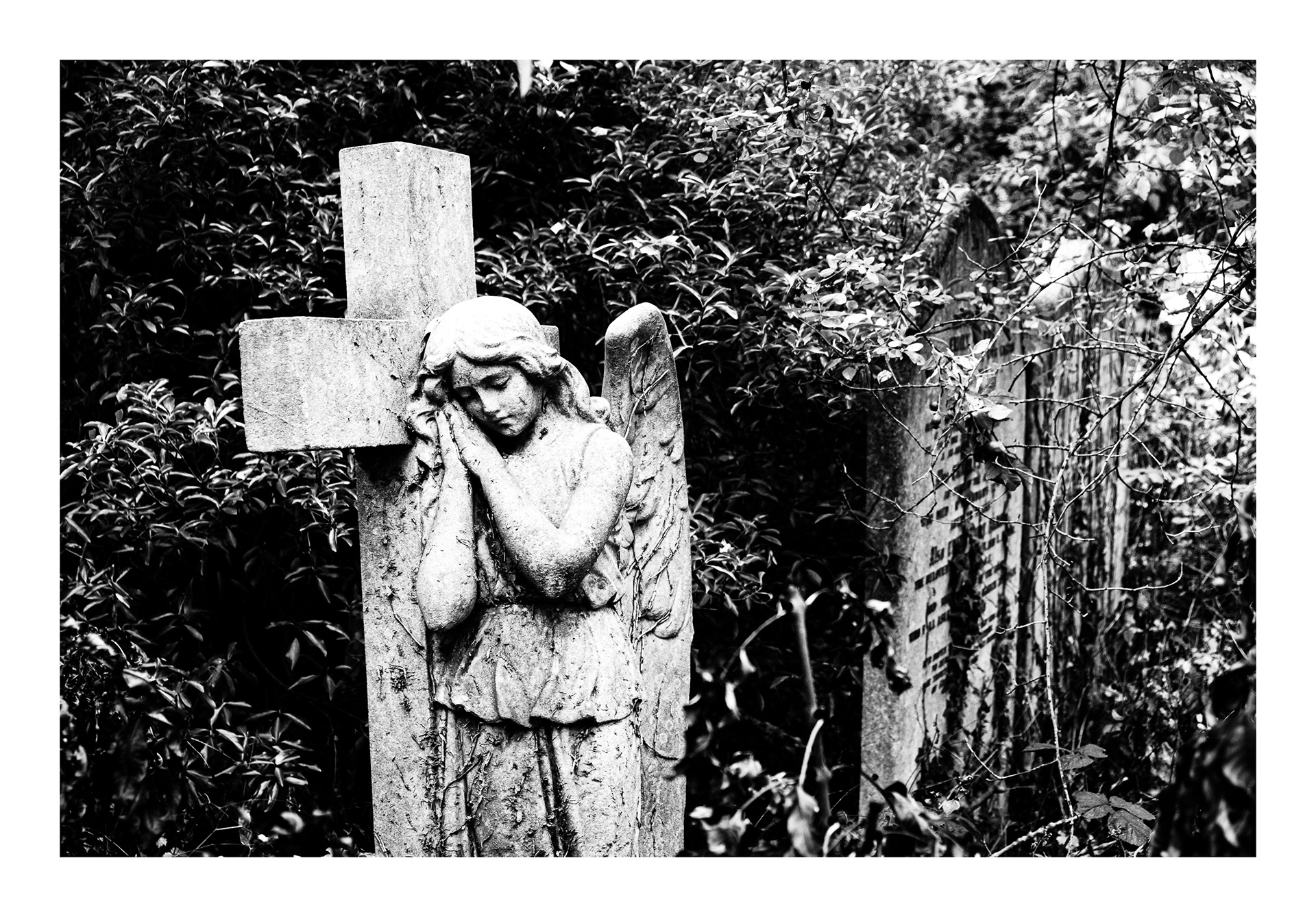

Today, nearly two centuries later, the Magnificent Seven Cemeteries have evolved beyond their original purpose. They stand as historic landmarks, their monuments and tombs weathered by time, their once-ordered avenues now softened by creeping ivy, wildflowers, and towering trees. In places, nature seems to reclaim what was borrowed, as if gently protecting the eternal sleep of those interred within. Time has eroded the finely carved details of angelic sculptures, headstones tilt and crumble, and vines weave through intricate wrought iron gates. Yet, rather than decay alone, this transformation speaks of continuity—of life coexisting with death.

Each of these cemeteries tells a different story. Highgate, the most opulent and best preserved, has become a well-known tourist attraction, while others, like Tower Hamlets, bear the marks of neglect, their inscriptions fading into oblivion. Kensal Green, Brompton, West Norwood, Nunhead, and Abney Park each carry their own unique blend of grandeur, mystery, and quiet repose. Once intended as places of mourning, they now serve as sanctuaries for wildlife, havens for quiet reflection, and, in many ways, open-air museums preserving a lost era’s perception of mortality.

The Magnificent Seven Cemeteries of London are more than burial grounds. They are windows into the past, offering us a glimpse of Victorian rituals, architecture, and reverence for the dead. As we walk their paths, we step into a world that no longer belongs to our time—one where grief was etched in marble, and where nature, in its slow and steady embrace, reminds us that all things must return to the earth.

Kensal Green Cemetery (1833)

West Notwood Cemetery (1837)

Highgate Cemetery (1839)

Abney Park Cemetery (1840)

Brompton Cemetery (1840)

Nunhead Cemetery (1840)

Tower Hamlets Cemetery (1841)